1. Introduction

1.1 Chemical Composition of Raw Beans

- Coffea arabica(아라비카 커피)와 Coffea canephora (로부스타 커피)의 콩들은

🔸 질량이 100mg에서부터 200mg 이상까지 다양하다.

🔸 지리적 원산지에 연관된 차이의 어떤 증거들도 있다.

🔸 두 가지 종들은 화학적 조성들에서 량적으로나 질적으로 차이를 보인다. - Arabica ➡ more lipids, more trigonelline

Robusta ➡ more caffeine, more chlorogenic acids - 한 종에만 특유한 비주요 성분들도 식별되어져 왔다.

- 커피 생두의 화학적 조성 ➡ Table 3.14

1.2 Chemical Composition of Green, Roasted, and Instant Coffee

2. Water content

- 건식법이나 습식법으로 가공된 green coffee의 수분 함량(water content)은

■ 보관 동안의 수분 활성도(water activity)와 안정성(stability)에 영향을 미친다.

■ 유럽에서는 정제된 커피 생두의 수분 함량은

■ 9%~13%에 이른다. - Dry-processed robusta coffees (건식법으로 처리된 로부스타 커피들) (Vietnam)

⇒ 때로는 더 높은 함수율 값들을 보이기도 한다. - 유럽커피연합(European Coffee Federation)은

➡ 보관과 수송을 위해 함수율(moisture level)을 12.5% 로 제안하고 있다. - 커피 생두의 함수율이 10% 미만인 경우에는

➡ 발아력(germinating power)이 떨어지고 나아가

➡ 콩이 크랙(crack, 갈라짐) 형성을 나타낼 수 있다. - 함수율이 12.5%를 넘으면,

➡ 미생물 감염의 상당한 위험이 존재한다. - 함수율 분석을 위한 국제적 준거 방법이

➡ 현재 이용 가능한 빠른 방법들을 표준화하는데 사용되어져야 한다.

3. Ash and Minerals

- 커피의 미네랄 성분 함량은 약 4%정도이다.

● Arabica 3.6%~4.5%

● Robusta 3.6~4.8% - 이 가운데 Potassium (칼륨) ➡ 커피가 함유하는 미네랄 성분 전체의 40%를 차지.

- 커피의 미네랄 성분 함량은 Table 3.2에 나타난 바와 같이,

➡ Wet-processed arabica에서 보다

➡ Dry-processed robusta and arabica에서 약간 더 높다.

- Table 3.15에는

➡ 커피 생두의 주요 미네랄들이 나와 있다.

➡ 칼륨, 칼슘, 마그네슘, 인산(인산염), 황(황산염) - 시비(fertilizing)는 ⇒ 이러한 함량들을 변화시킬 수도 있다.

- 음식들 가운데에서 루비듐(rubidium) 함유율이 가장 높은 것으로 분석된 것이 ➡ 커피

● arabica 25.5~182 mg/kg dry matter

● robusta 6.6~95.2 mg/kg dry matter - Quijano Rico and Spettel (1975)의 연구

➡ 커피 내의 copper(구리), strontium(스트론튬), barium(바륨)의 함량을 측정,

➡ 아라비카에서보다 로부스타에서 더 함량이 높았음. - 커피가 운송 도중에 바닷물에 오염되지 않았다면, ➡ Sodium and chloride content은 낮다.

- Ash

➡ 약 90%는 물에 녹을 수 있으며,

➡ 로스팅에서 거의 없어지지 않고 커피 추출액으로 담겨 들어간다. - 인스턴트 커피의 추출 수율 은 블렌드와 제조 손실이 알려진 경우에는

➡ potassium 함량에 의해 추정될 수 있다(R. J. Clarke, L. J. Walker, 7th ASIC, 1975, 159). - 미량의 금속 농도 특히 manganese 농도는

➡ 컵 품질과 상관될 수 있다 (R. Macrae, M. Petracco, E. Illy, 15th ASIC 1993, 650).

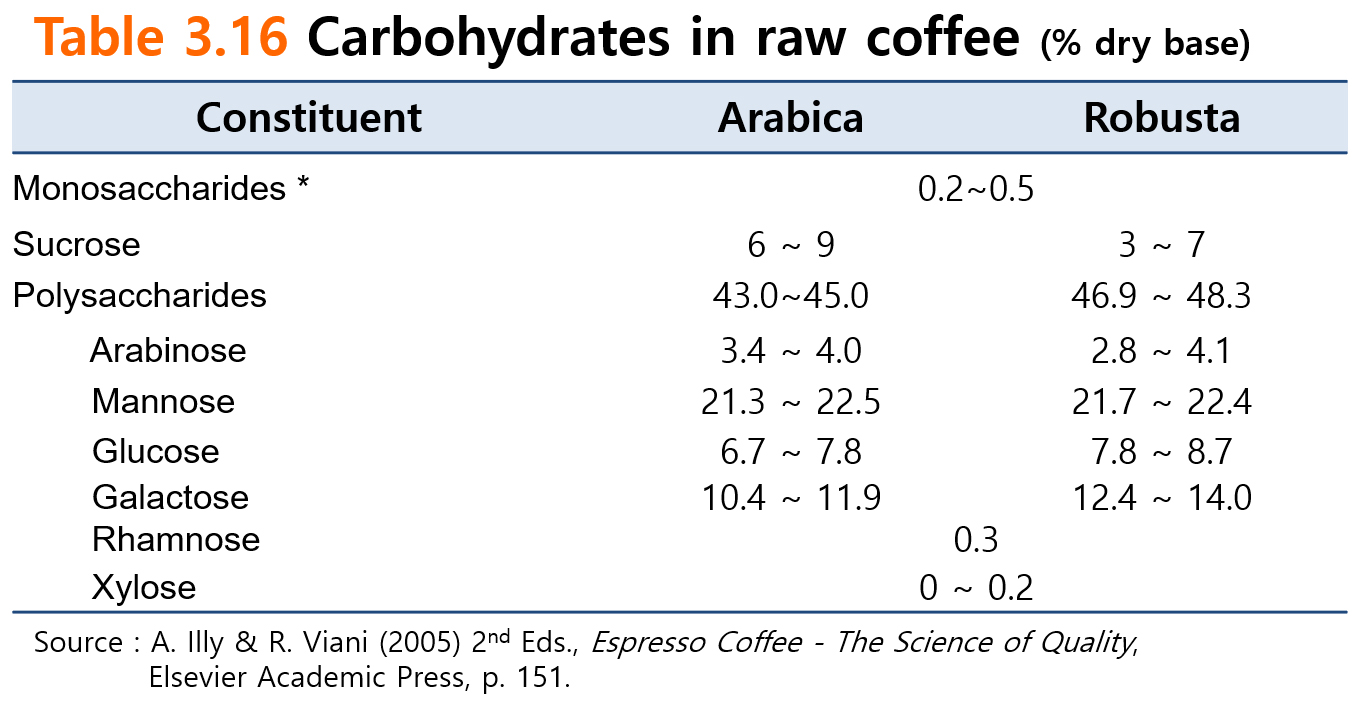

4. Carbohydrates

- Total amount of carbohydrates (커피 생두의 탄수화물 총량)은 무수물 기준에서

➡ 약 50%를 나타낸다. - 커피 생두의 탄수화물 조성(구성)은

➡ Table 3.16과 Table 3.16-1에 나타난 바와 같이 여러 가지

多糖類,

寡糖類,

單糖類로 복합적으로 이뤄져 있다.

- Silwar and Lüllman (1988, 1989)는

➡ 13개 생산국 별 20가지의 커피 생두 샘플들의 저분자 탄수화물 특성을 가려내기 위해

HPLC-기반적 방법을 사용하여 분석했다.

➡ 그들의 핵심적 발견 사항은 다음과 같다 ;

(1) 수크로오스 함량 분석

Arabica 샘플 ⇒ 6.25%에서 8.45%까지 나타났고,

Robusta 샘플 ⇒ 3.9%에서 4.85%로 나타났다.

(2) 기타 단당류 식별 : 수크로오스 이외에도

소량의 fructose, glucose, mannose, arabinose, 그리고 rhamnose와 같은

단당류들이 파악되었다.

(3) 이런 환원당들(reducing sugars)은

로브스타 커피에서 더 높게 함유되어 있는 것으로 나타났다.

(4) 수크로오스 그리고 말토오스(maltose)의 최저 함량(0.01%)를 함유한

한가지 로부스타를 제외하고는,

커피 생두에서의 'flatulent sugars', raffinose 또는 stachyose와 같은

다른 단순한 과당류(oligosaccharides)에 대한 증거는 없었다. - Mazzafera (1999)의 연구

➡ 수크로오스 함량이 숙과도(degree of ripening)에 따라 증가할 것이라고 기대되었는데,

이는 결점두들에서는 분명하게 나타났다.

➡ 브라질 로부스타 커피의 immature-black beans와 immature-green beans의 경우에

수크로오스 함량이 각각 정상 콩의 1/3과 1/5 수준으로 나타났다.

➡ 베트남 로부스타 커피에서도 이런 현상이 관찰되었는데,

샘플에서 분리되어진 black beans는 0.9% 수크로오스 함량을 보였고,

나머지 정상 콩들에서는 4.0%의 함량을 보였다. - Illy and Viani (1995)의 연구

Glucose 함량은

➡ 아로마 수준과 부정적으로 상관되는 것으로 나타났고

➡ 최종 컵 감미도(sweetness)와는 긍정적으로 상관되는 것으로 나타났다. - Franz and Maier(1993, 1994)의 연구

inositol triphosphate (3인산 이노시톨), inositol tetraphosphate (4인산 이노시톨),

inositol pentaphosphate (5인산 이노시톨), 그리고

inositol hexa-phosphate (6인산 이노시톨 = phytic acid, 파이틱산)를 파악하였다.

➡ 로부스타에서의 total inositol phosphate 함량은 0.34%~0.40% 범위로 나타나

➡ 아라비카의 경우 0.28%~0.32% 범위 보다 더 높은 경향이 있었다.

- Noyes and Chu (1993)의 연구

➡ Polyalcohol (폴리 알코올, polyol = 폴리올)도 커피 생두에서 발견되었다.

➡ 브라질 로부스타 커피와 아라비카 커피의 블렌드들에서 낮은 수준의 mannitol(마니톨)을 발견하였다

(평균 함량 0.027%). - 커피 생두 다당류(polysaccharides)의 화학 구조를

Bradbury and Halliday (1987, 1990)와

Fischer et al.(2000) 등이 집중적으로 연구한 바 있다. - 커피 생두에는 다른 식물의 경우에 공통적인 다당류인 starch 나 pectin도 존재하지만

➡ 커피 콩에서 매우 적은 수준만 있을 뿐이다. - Xylose의 중합체로 특징 지울 수 있는 lignin(리그닌)은 씨앗에는 존재하지 않는다.

5. Glycosides

- 1970년대, Spiteller 연구 그룹(Ludwig et al., 1975; Obermann and Spiteller, 1976)에 의해,

커피 생두와 배전 커피에서

➡ 일련의 다이터핀 배당체들(a series of diterpene glycosides)인 atractylglycosides가 파악되었다. - Maier and Wewetzer (1978)의 연구와

Aeschbacj et al. (1982)의 연구

➡ KA I, KA II, KA III라고 명명한 이 화합물 군의 주요 구성 성분들의 커피내 함량을 확인하였다. - Bradbury and Balzer (1999)의 연구

➡ 커피 생두 내의 이러한 배당체들이 실제로 C-4에서 2개의 카르복실기(two carboxyl groups)를

가지고 있는 것을 확인

➡ 그리고 결과적으로 그 화합물이 carboxyatractylglycosides인 것으로 식별되었다.

➡ 그 카르복실기는 labile(불안정)하여, 왜 앞선 연구들이 단지 atractyl form만을 관찰했는지를 설명

➡ 아라비카 콩은 로부스타 콩보다 배당체를 더 유의하게 많이 가지고 있다.

6. Carboxylic acids

- Table 3.17

➡ 여러 생두들의 퀴닉酸, 말릭酸, 씨트릭酸, 포스퍼릭酸의 함량들을 보여주고 있음.

➡ 출처 : Kampmann & Mailer (1982), Scholze & Maier (1983, 1984),

Engelhardt & Maier (1984, 1985), Whohrmann (1997).

- Van der Stegen and Van Duijn (1987)에 따르면,

➡ 아라비카 커피와 로부스타 커피에서 카르복실酸類 전체 함량은 비슷하다.

➡ 클로로겐산류에서 지방족 酸 부분(aliphatic acid moiety)인 Quinic acid도 유리상태로 존재한다.

그 함량은 아마 프로세싱, 발효, 그리고 에이지와 같은 요인들에 의해 영향을 받을 것이다.

➡ 유리 퀴닉산 함량은 오래된 콩에서는 1.5%까지도 증가할 수 있다. - 퀴닉 산 이외에, 커피 생두의 주요 산들에는

➡ malic acid, citric acid, 그리고 phosphoric acid가 있다. - Bähre (1997), Bähre and Maier (1999) 연구

➡ 비주요 커피 산들(minor coffee acids)이 식별되었다. - 추출된 커피(brewed coffees)의 Acidity(애씨더티, 산미)는

➡ 중요한 감각수용적 특성(organoleptic character)이며,

➡ 이는 케냐 커피와 같이 최고의 high grown 아라비카 커피들에 관련된다.

7. Chlorogenic acids

- Chlorogenic acids(클로로겐산류)는

➡ 퀴닉산(quinic acid)으로 에스테르化된 일단의 페놀산류이다 (Clifford, 1999; Parliament, 2000).

➡ a group of phenolic acids esterified to quinic acid. - CGAs는 ➡ 이 산화합물군은 커피 생두 무게의 10%까지도 차지한다.

- Mono-caffeoylquinic acid, Di-caffeolyquinic acid가 커피에서 식별되었다.

➡ Quinic acid의 3-position, 4-position 5-position에서의 치환(substitution)으로 파악되었음. - 이러한 커피의 페놀산 부분(phenolic acid fraction)의 구성은 다음과 같이 이뤄져 있다(Figure 3.29 참조).

➡ Caffeoly-acids

➡ p-coumaroyl-acid

➡ Feruloyl-acids - 커피에서 이 성분들은 본질적으로 monoesters(모노에스테르)와 diesters(다이에스테르)이다.

➡ monoesters는

■ unripe stage에서부터 semi-ripe stage 동안에 감소하다가

■ ripe stage로 가면서 증가한다.

■ slightly overripe stage에서 증가한다.

(이는 dry processing에서보다 wet processing에서 더욱 중요하다)

(Castel de Menezes and Clifford, 1988)

8. Amino acids, peptides and proteins

- Free amino acids (유리 아미노산류) ➡ 커피 생두에서 약 1% 수준에서 존재(Trautwein, 1987).

- Post-harvest treatments (수확후 처치)

➡ 개별 유리 아미노산들의 함량에 영향을 미침.

➡ Arnold(1995)의 연구에서 추정된 바 있음. - Arnold(1995)의 연구는 아라비카 커피 8가지 샘플들로 추정되었다.

➡ Total free amino acids는 40℃에서 건조한 후에 명확한 변화를 보이지 않았지만,

➡ 어떤 아미노산들의 개별 함량 변화는, 특히

⇒ glutamic acid는 약 50% 증가했고

⇒ aspartic acid는 주로 감소했고,

⇒ hydrophobic acids (valine, phenylalanine, leucine, isoleucine)는 일반적으로 증가했다. - Lipke (1999)의 연구

➡ 리프크는 몇 가지 커피 펩티드들(peptides)을 분리해내어 특징을 분석한 바 있다. - Pokornv et al.(1975)의 연구

➡ 커피 생두의 보관 중, 특히 높은 온도에서의 보관 중에 발생하는 변화를 발견.

➡ proteolysis(단백질 가수분해)로 인한 변화 (예, alanine, isoleucine, tryosine의 증가)와

➡ 비효소적 갈변 반응(non-enzymatic browning reactions)에 의한

유리 아미노산들의 손실로 인한 변화. - 커피 생두 속의 단백질 구성

- 대다수의 단백질들 ➡ 150,000 Daltons가 넘는 분자량을 가지고 있다.

- Crude protein (조단백질)

➡ total nitrogen content (총 질소 함량)로 계산했을 때

➡ caffeine에 대해 조정되어야 하고

➡ 이상적으로는 trigonelline nitrogen에 대해서도 조정되어야 한다.

➡ 만일 그러한 조정이 이루어진다면, 커피 생두내의 단백질 함량은 10% 가까이 되며

➡ 커피 종별로 량적 차이와 질적 차이가 있으며,

➡ 프로세싱에 기인할 수 있는 유의한 효과는 없다. - Mazzafera (1999)는

➡ immature beans에서 보다는

mature beans에서 더 높은 단백질 함량을 발견했다. - 커피 생두 내의 효소들로 파악된 것들은 :

α-galactosidase,

malate dehydrogenase,

acid phosphatase,

peroxidase,

➡ 그리고 더 집약적으로

커피 생두의 품질 지표로서 → polyphenol oxidase/tyrosinase/catechol oxidase (Clifford, 1985).

➡ Polyphenol oxidase는

결점두의 탈색 원인이며,

이는 클로로겐산류 산화의 활성화(chlorogenic acids의 oxidation를 catalysing)에 의해 유발된다.

9. Non-protein nitrogen

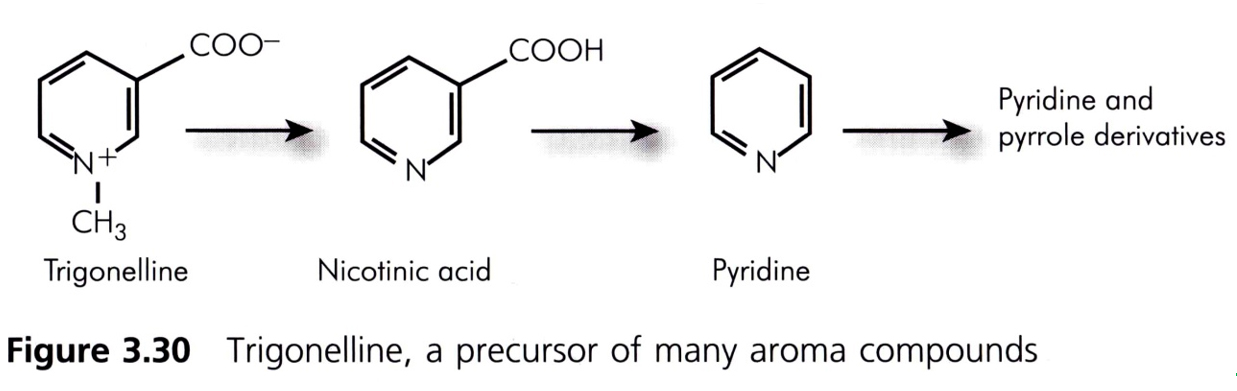

9.1 Trigonelline

- Raw coffee는 트리고넬린을 함유하고 있다.

➡ 이는 caffeine의 약 25% 정도의 쓴맛을 낸다.

▣ arabica : 06 ~ 1.3%

▣ robusta : 0.3 ~ 0.9% - 트리고넬린 ➡ C7H7NO2의 화학식을 가지는 식물성 염기의 일종.

- 트리고넬린 ➡ 비타민 B3인 niacin(니아신)의 니트로겐 원자에 메틸 그룹이 결합하여 형성되는 inner salt이다.

- 트리고넬린 ➡ urine에서 떨어져 나오는 niacin의 대사작용의 산물이다.

- 트리고넬린 ➡ 많은 아로마 화합물의 전구물질이다.

- 트리고넬린은 배전 시에

➡ nicotinic acid (niacin 또는 vitamin PP),

➡ pyridine (피리딘), 그리고

➡ 기타 volatile aroma constituents (휘발성 아로마 성분들)로 분해되고

➡ 나머지는 쉽게 추출된다. - Stennert and Mailer (1994)의 연구

➡ Dewaxing, decaffeination 절차, Steaming은

트리고넬린 함량 변화에 영향을 미치지 않는다는 것을 발견.

9.2 Caffeine and purine alkaloids

- Caffeine (카페인)은 ➡ green coffee의 주된 purine이다.

- Caffeine (카페인)은

➡ 화학식 C8H10O2N4.

➡ 3개의 메틸기를 가진 크산틴 구조이다. - Caffeine (카페인)은

➡ π-electron complex에 의해 chlorogenic acids와 연결되어 있다 (Horman and Viani, 1972). - Average content of caffeine (카페인 평균 함유율)

⊙ arabica 1.2 ~ 1.3%

⊙ robusta 2.2 ~ 2.4%

➡ High intra-specific variability (종내에서의 차이가 많다)

➡ showing a marked inter-specific difference (분명한 종간차이를 보인다)

➡ 어떤 비상업적 야생종들에서는

카페인이 없거나 미량으로만 존재하는 경우도 있음.

- Coffee는

➡ Caffeine (카페인) 이외에도

➡ 3가지의 dimethylxanthines (디메틸크산틴즈)를 가지고 있다. - Coffee 생두에 함유된 흥분작용을 가진 purine 염기에는

➡ 카페인 이외에도

아래 [Table]에 열거된 것들과 같은 성분들도 있다. - 다른 미량의 purines

➡ arabica 보다는 robusta에(특히, immature beans에) 더 많은 량으로 존재 - Kappeler & Baumann (1986)의 연구

➡ Theophylline, theobromine, liberine, theacrine의 함량이

➡ Unripe beans가 ripe beans 보다 더 큼을 발견. - Weidner & Maier (1999)의 연구 ➡ paraxanthine과 theacrine을 식별

- Prodolliet et al. (1998)의 연구

➡ 16개 국가들의 아라비카 생두와 로부스타 생두로부터 추출된 카페인 샘플들에서

➡ isotopic ratios (C, N, H)를 사용하여 커피의 지리적 원산지를 결정하고자 시도했음.

➡ 단일변량분석과 다변량 분석들의 수행 결과,

종들의 결정이나 원산지 국가 결정 모두 할 수 없었음.

10. Lipids

- 지질 함량 (lipid content)

➡ 아라비카 커피 생두의 경우는 15%~18%, 평균 약 15%이다.

➡ 로부스타 커피 생두의 경우는 8–12 %, 평균 10% (훨씬 더 작다).

➡ 실제 범위는 더 작을 수도 있다.

➡ 비누화 불능 물질의 함량이 비교적 높다. - 지질의 구성

➡ 지질은 화학적으로 다른 2가지의 fractions으로 나뉠 수 있다.

▣ 왁스 = 콩의 가장 바깥 쪽을 이루고 있음(0.2%~0.3%)

▣ 오일 = 배젖 내부에 위치. - 아라비카와 로부스타의 지질 조성은 ➡ 질적으로 약간만 차이가 날뿐이다.

- 지질의 존재 위치

▣ 대부분의 지질(커피 오일)은 ➡ endosperm(배젖, 배유, 내유) 내에 위치한다.

▣ 소량의 지질, 즉 coffee wax만이 ➡ 콩의 outer layer(표층)에 존재한다. - 조지질의 생성(yield of crude lipids)에 영향 미치는 요인들은

▣ 콩의 조성 (bean composition)

▣ 추출 조건 (extraction conditions), 특히 입자 크기(particle size)와 표면적(surface area)

▣ 솔벤트의 선정(choice of solvent)과 추출 시간(duration of extraction) - 커피 오일은

➡ 보통 식용 야채들에서 발견되는 것과 비슷한 비율로

➡ 주로 지방산들(fatty acids)을 함유하는 트리글리세리드(triglycerides)로 구성된다. - 커피 오일의 비교적 큰 비누화 불능 부분(unsaponifiable fraction)은

➡ kaurane family의 diterpenes (다이터핀즈)에서 풍부하다.

➡ 커피 오일의 Kaurane family에는 주로

▣ cafestol (카페스톨),

▣ kahweol (카훼올) 그리고

▣ 16-O-methylcafestol 이 있으며,

➡ 이 물질들은 각기 다른 생리효과 때문에 최근 더욱 더 많은 관심을 받아왔다.

➡ 더욱이, 16-O-methylcafestol은

커피 블렌드에서의 로부스타 함량을 나타내는 신뢰 가능한 지표로서 사용될 수 있다. - 비누화불능 부분의 일부인 sterols 가운데에서도,

➡ 여러 가지 desmethylsterols,

➡ methylsterols, 그리고

➡ dimethylsterols이 식별되어 왔다. - 커피 생두의 지질부분의 조성은 Table 3.18에 나타나 있다.

10.1 Fatty acids

- 커피 생두의 지방산들(fatty acids)은

┌ ⊙ 대부분이 트리글리세리드(triglycerides)내의 그릴세롤 에스테르(glycerol esters)로서 존재하며,

├ ⊙ 약 20% 정도가 다이터핀즈(diterpenes)로 에스테르化되며,

└ ⊙ 적은 비율이 스테롤 에스테르(sterol esters)로서 존재한다. - 주요 지방산들은

➡ linoleic acid (40–45 %)와

➡ palmitic acid (25~35%). - Folstar et al.(1975), Speer et al.(1993)의 연구

➡ 트리글리세리드의 지방산들과

➡ 디터핀 에스테르를 자세하게 연구. - Picard et al.(1984)의 연구

➡ 스테롤 내의 지방산들을 식별함. - 커피 내의 유리 지방산들(FFA, free fatty acids)의 존재는

➡ 여러 연구자들이 설명.

Kaufmann and Hamsagar, 1962; Calzolari and Cerma, 1963;

Carisano and Gariboldi, 1964; Wajda and Walczyk, 1978

➡ 이 연구자들의 데이터는 모두 acid value에 의해 표현됨.

➡ 지방 분석에 간접적인 결정 절차를 사용한 것이었음.

- Speer et al. (1993)의 연구

= 유리 지방산들을 직접적으로 결정하는 방법을 개발했음

(method of the direct determination of free fatty acids). - BioBeads S-X3를 이용한 the gel chromatographic system을 사용하여,

tertiary butyl methyl로 추출된 커피 지질들은 3가지의 fractions로 나눠질 수 있음.

1) a fraction with the triglycerols (트리글리세롤을 가진 부분)

2) a fraction containing the diterpene fatty acid esters (디터핀 지방산 에스테르를 함유하고 있는 부분), and

3) one with the free fatty acids (유리지방산들을 가지고 있는 부분). - 9가지의 유리 지방산들이 검출되었으며,

아라비카와 로부스타 커피에서 비슷하게 분포했음을 확인. - 두 커피 종에서 모두 주요 지방산들은 ➡ C18:2 and C16으로 나타났음.

- 큰 비율로 검출된 지방산들은 ➡ C18, C18:1, C20 and C22

- 미량으로 나타난 것들은 ➡ C14, C18:3 and C24.

- 아라비카와 로부스타 간의 차이는

➡ stearic acid와 oleic acid 함량이 chromatograms상에서 비교되는 경우에서만 보이게 됐음.

➡ 로부스타에서 stearic acid의 비율이 oleic acid의 비율보다 현저하게 더 작았고,

아라비카에서는 이 두 산들의 비율이 거의 같았음.

➡ 비율 [stearic acid / oleic acid]은

커피 블렌드에서 로부스타의 함량을 나타내주는 첫 번째 지표가 될 수 있을 것임.

10.2 Diterpenes

- 커피 내의 주요 디터핀(다이테르펜, 디이터핀)은

➡ kaurane skeleton에 기반을 둔

➡ pentacyclic diterpene alcohols이다. - 여러 연구그룹들에 의해 2가지 커피 디터핀의 구조가 먼저 밝혀졌었다.

Bengis and Anderson (1932), Chakravorty et al. (1943), Wettstein et al. (1945),

Haworth and Johnstone (1957), Finnegan and Djerassi (1960)

┌ kahweol

└ cafestol

➡ 이 두가지는 모두 산류, 열, 빛에 민감하고,

➡ 특히 kahweol은 정제된 형태에서 불안정하다. - 1989년에, 로부스타 커피로부터

16-O-methylcafestol (16-OMC)가 분리되었고

그 구조가 합성에 의해 설명되었다.

(Speer and Mischnick, 1989; Speer and Mischnick-Lübbecke, 1989). - 2001년에는

추가적인 디터핀인 16-O-methylkahweol가 로부스타 커피콩들에서

Kölling-Speer and Speer (2001)에 의해 발견되었다. - 이러한 디터핀들의 구조식들은 Figure 3.32에 나와 있다.

- Arabica 커피는 ➡ cafestol과 kahweol을 함유하고 있다.

- Robusta 커피는

➡ cafestol과, 소량의 kahweol을 함유하고,

➡ 추가적으로 16-O-methylcafestol (16-OMC)과

미량의 16-O-methylkahweol을 가지고 있다(로부스타에서만 발견). - 아라비카 콩에서의 16-OMC 부재는 여러 연구에서 확인된 바 있다.

▣ White (1995), Frega et al. (1994), Trouche et al. (1997) and Kamm et al. (2002)

▣ 16-OMC는 로스팅 과정 동안의 안정성을 가지며, 그 때문에

▣ 아라비카 블렌드 내의 2% 미만의 로부스타 존재를 검출하는데 사용될 수 있다. - 디터핀들인 cafestol, kahweol, 그리고 16-OMC는

➡ 주로 여러 지방산들로 에스테르화된다.

➡ 그런 것들의 유리 형태에서, 그들은 커피 오일의 비주류 성분으로만 발생한다. - free cafestol과 free kahweol은 모두

➡ 아라비카 커피에 존재하며,

➡ cafestol이 주요한 성분이다. - 로부스타 커피에서는

➡ free cafestol 함량은 16-OMC 보다 약간 더 높고,

➡ free kahweol은 미량으로만 존재하거나 없다. - free diterpenes와 비누화 후의 total diterpenes를 비교해 보면,

➡ 아라비카에서는 비율들이 0.7~2.5%

➡ 로부스타에서는 비율이 1.1~3.5%를 보인다.

➡ 만일 그 차이가 프로세싱 기법 때문이거나 종들 때문인 것이라면

검증하기 위해 실험을 해보아야 한다. - Diterpene fatty acid esters:

- 지방산 에스테르들이 그 동안 보고되어 왔다.

(Kaufmann and Hamsagar, 1962a; Folstar et al., 1975; Folstar, 1985; Pettitt, 1987;

Speer, 1991, 1995; Kurzrock and Speer, 1997a, 1997b)

▣ C14, C16, C18, C18:1, C18:2, C18:3, C20, C22, C24 와 같은 지방산을 가진

Cafestol esters도 식별되었고

▣ fatty acid C20:1을 가진에스테르도 식별되었으며

▣ C17, C19, C21 and C23. 과 같은 어떤 홀수가 붙은 지방산들도 보고되었다. - 개별 디터핀 에스테르들(diterpene esters)은 ➡ 커피 오일내에 불규칙적인 량으로 존재한다.

▣ 홀수 지방산 에스테르들은 비주류 성분들인 반면에

▣ palmitic, linoleic, oleic, stearic, arachidic, and behenic acid으로

에스테르화된 디터핀들은

더 많은 향으로 존재한다 (Speer, 1991; Speer, 1995; Kurzrock and Speer, 1997a). - 그래서 초점은

➡ 각 디터핀들의 거의 98%의 합을 이루는

➡ 6가지 디터핀들에 집중되었는데,

➡ 이들 6가지 에스테르들의 아라비카 커피의 분포는 Table 3.19와 같이 나타났다. - 이 6가지 cafestol esters의 총 함량은

▣ 합계하여 9.4-21.2 g.kg-1 dry weight 범위에 이르고,

▣ 이는 다른 아라비카 커피들의 경우에

➡ cafestol 5.2-11.8 g.kg-1에 해당한다.

▣ 로부스타 커피에서는,

➡ 함량이 2.2 and 7.6 g.kg-1 dry weight로 결정되었고,

➡ 이는 1.2-4.2 g.kg-1 cafestol에 해당하며,

아라비카 커피의 경우에서보다 현저하게 작다.

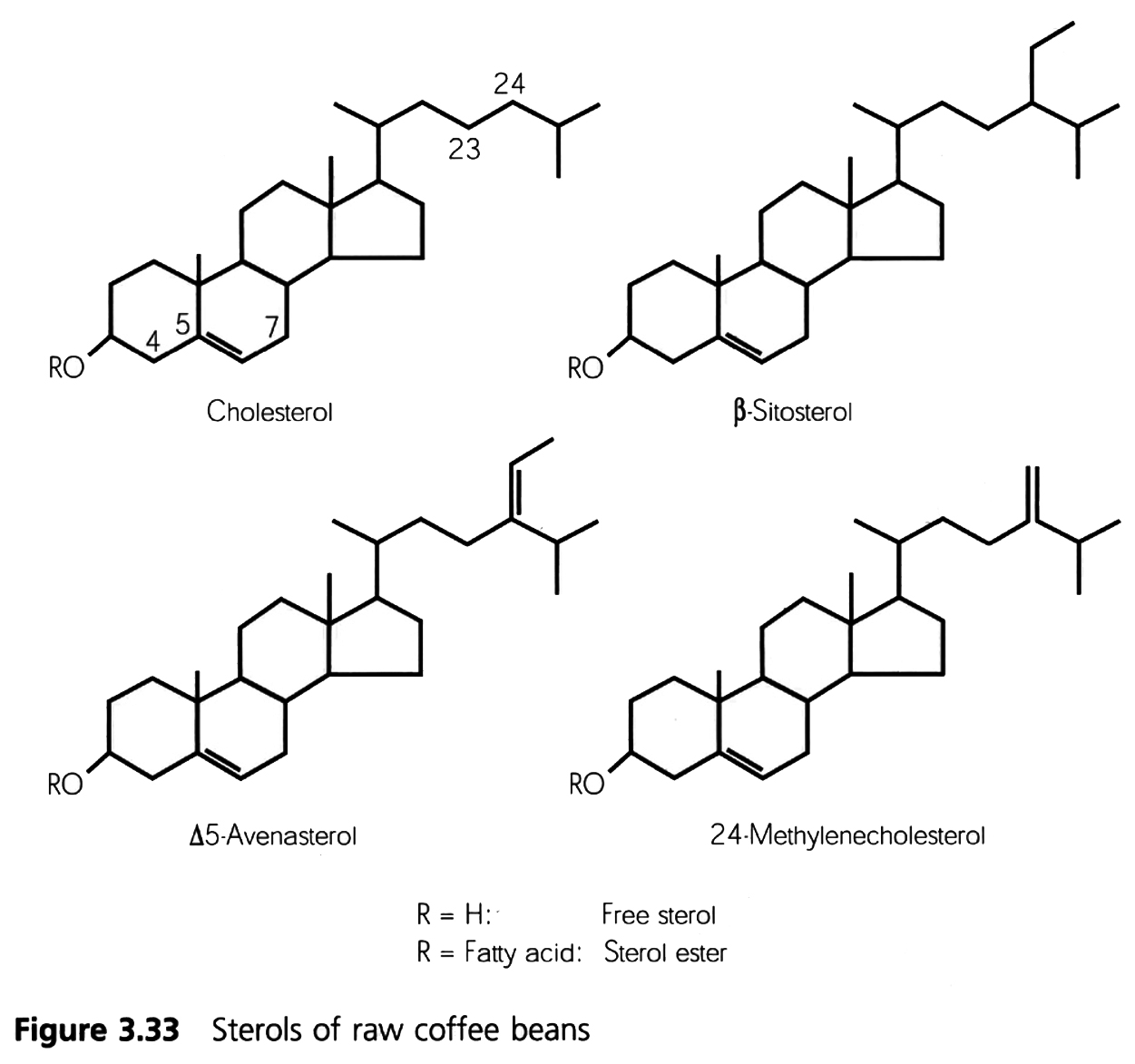

10.3 Sterols

- 커피는 ➡ 여러 가지 다양한 스테롤들을 함유하고 있다.

다른 씨앗 오일들도 공통적으로 가지고 있듯이. - Figure 3.33 ➡ 커피 생두의 스테롤들

- 그 동안 식별되어 온 스테롤들

▣ 4-desmethylsterols,

▣ 여러 가지 4-methyl-dimethylsterols,

▣ 여러 가지 4,4-dimethylsterols. - 커피 스테롤들은 두 가지 형태 모두로 발견되어 왔다 ;

● 유리 형태 (free form) --- 약 40%

● 에스테르화된 형태(esterified form) --- 약 60%

(Nagasampagi et al., 1971; Itoh et al., 1973a,b, Tiscornia et al., 1973;

Picard et al., 1984; Duplatre et al., 1984; Mariani and Fedeli, 1991;

Frega et al., 1994; Speer and Kölling-Speer, 2001). - Picard et al. (1984)의 연구

➡ sterol esters의 개별 지방산들을 연구했다.

➡ triacylglycerols의 경우와 비슷한 비율 분포를 가지는

Stearic acid, palmitic acid 그리고 oleic acid이 주요한 화합물로 나타났다. - Desmethylsterols이

● total sterol fraction의 90%를 나타낸다.

● 이는 지질의 1.5%~2.4%의 범위에 해당.

● 어떤 경우에는 더 높은 비율로 발견되기도 한다 (예, 5.4%, Nagasmppagi et al. 1971). - Table 3.20 ➡ 여러 로부스타와 아라비카 커피 샘플에서의

주요 Desmethylsterols의 평균 분포(%)

- 주요 스테롤은

➡ 약 50%를 차지하는 b-sitosterol이며,

➡ 그 다음이 stigmasterol과 campesterol이다. - 아라비카 커피에서보다 로부스타 커피에서 훨씬 더 높게 나오는

24-Methylenecholesterol과

D5-avenasterol이 ➡ 커피 블렌드 연구들에 적합하다.

➡ 왜냐하면, 배전 과정은 스테롤 량과 분포에 거의 영향을 미치지 않기 때문이다.

➡ 그러나, 천연 함량의 변동 때문에,

아라비카 커피 혼합에서 로부스타 비율을 가리는데 사용하는 것은 20% 정도만 타당할 뿐이다.

10.4 Tocopherols

- Folstar et al. (1977)의 연구

▣ 커피 오일 내의 tocopherols(토코페놀)의 존재는 ➡ Folstar et al. (1977)에 의해 처음으로 설명되었다.

▣ a-tocopherol이 ➡ 분명하게 식별되었고

▣ b-tocopherol과

g-tocopherol은 ➡ TLC와 GC에 의해 분리되지 않은채 하나의 그룹으로서 고려되었다.

▣ 발견된 농도

a-tocopherol ➡ 89-188 mg.kg-1 oil

b-tocopherol + g-tocopherol ➡ 252-530 mg.kg-1 oil. - Cros et al. (1985)의 연구

➡ HPLC의 합으로서 b-tocopherol과 g-tocopherol을 확인 - Aoyama et al.(1988)의 연구

⊙ 여러 커피 품종들에서의 a-, b- and g-tocopherols을 분석해본 결과,

➡ 거의 2:4:0.1의 비율로 존재.

⊙ 총 함량은 ➡ 약 5.5-6.9 mg/100 g 이었음.

⊙ 커피 콩에서는 ➡ a-tocopherol이 지배적임. 이는 다른 야채들과 과일들의 경우와 대조적임. - Ogawa et al. (1989)의 연구

⊙ 14가지 커피 콩들, 이들의 배전두와 우려낸 커피액, 그리고 38가지 인스턴트 커피들에서의

토코페롤 함량을 HPLC에 의해 확인.

⊙ 커피 생두에서의 토코페롤 최대값은 ➡ 15.7 mg.100 g-1이었고

평균은 ➡ 11.9 mg.100 g-1로 나타났음.

⊙ a-tocopherol 함량은 ➡ 2.3-4.5 mg.100 g-1,

⊙ b-tocopherol 함량은 ➡ 3.2-11.4 mg.100 g-1,

⊙ g-tocopherol, d- tocopherol은 ➡ 발견되지 않았음.

⊙ 로스팅은 함량을 감소시킴 :

┌ a-tocopherol을 ➡ 79-100 %로,

├ b-tocopherol를 ➡ 84-100 %로,

└ total tocopherols를 ➡ 89-99 %로. - Speer and Kölling-Speer(2001)의 연구

⊙ GC-MS를 이용하여, 어떤 로부스타 커피들에서 g-tocopherol가 검출되었음. - González et al. (2001)의 연구

⊙ 이해하기는 어렵지만, g-tocopherol의 량이 생두에서보다 배전커피에서 더욱 높게 발견되었음.

10.5 Coffee Wax

- 커피 생두의 표면은 엷은 왁스 층(waxy layer)으로 덮여 있다.

- 커피 생두 표면 왁스의 량은

➡ 전체 콩 무게의 약 0.2% ~ 0.3% 정도임.

➡ 전체 지질의 2-3%에 해당함. - 왁스 함량은

➡ dichloromerthane과 같은 chlorinated organic solvents를 사용한 추출에 의하여

온전한 커피 콩으로부터 얻어지는 것으로 일반적으로 정의됨. - 아라비카 커피 생두의 왁스 조성에 관한 최초의 탐구는

➡ Wurziger와 그의 동료들 (Dickhaut, 1966; Harms and Wurziger, 1968).

▣ 그들은 왁스의 petroleum ether 불용성 부분의 주성분은

➡ 소위 carboxylic acid-5-hydroxytryptamides (C-5HT)라고 하는 것.

➡ 이 물질 그룹 즉 amides of serotonine (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5HT)과

여러 길이의 체인들을 가진 지방산들을 최초로 소개.

▣ 그들은

➡ Arachidic acid (n = 18),

➡ Behenic acid (n = 20), 그리고

➡ Lignoceric acid (n = 22)를 가지는

3개의 carbonic acid 5-hydroxytryptamides (C-5HT)를

분리해내어 식별했음. (Figure 3.35 참조)

▣ 즉, arachidic acid (n=18), behenic acid (n=20), 그리고 lignoceric acid (n=22)가

5-HT의 주요 아미노기와 결합되어 있다. - Folstar et al. (1979; 1980)의 연구

▣ stearic acid-5HT (n=16),

ω-hydroxyaracgidic acid-5-hydrixytryptamide (n=18),

ω-hydroxybehenic acid 5-hydrixytryptamide (n=20)의 존재를 보고.

▣ Arachidic acid-5HT와

Behenic acid-5HT가 지배적이고,

다른 아미드들은 마이너 성분들에 불과함. - Figure 3.35 ➡ 3가지의 C-5-HT

- Wurziger(1973)의 연구

▣ Arabica coffees에서의 total C-5HT 함량 ➡ 500 ~ 2370 mg.kg-1 ➡ 로부스타보다 분명히 더 높음.

▣ Robusta coffees에서의 total C-5HT 함량 ➡ 565 - 1120 mg.kg-1,

▣ 30년 이상 장기 저장 기간은 ➡ 160 and 950 mg.kg-1의 낮은 총 함량으로 유도함. - Maier (1981)의 연구

▣ 아라비카 생두에서의 total C-5HT 함량 ➡ 500 ~ 2370 mg/kg

▣ 로부스타 생두에서의 total C-5HT 함량 ➡ 565 ~ 1120 mg/kg - 커피 콩에 대한 polishing, dewaxing, steaming 또는 decaffeinating과 같은

기술적 처리에 의한 왁스 층의 제거는

➡ C-5HT 총 함량의 감소 이외에도

➡ more digestible coffee brew를 초래한다.

(Behrens and Malorny, 1940; Wurziger, 1972; van der Steegen, 1979;

Fintelmann and Haase, 1977; Hunziker and Miserez, 1979; Corinaldesi et al., 1989). - C-5HT의 항산화 효과(antioxidant effects)가

➡ 커피 왁스를 식품에서 사용될 수 있는 천연 항산화 물질로서 사용하는 것에 대해 큰 관심을 유도해왔음.

➡ C-5HT는 항산화 특성을 가지고 있다.

(Lehmann et al., 1968; Bertholet and Hirsbrunner, 1984)

10.6 Other Compounds

- Kaufmann and Sen Gupta (1964)의 연구

▨ 커피 오일의 비누화 불능 부분(unsaponifiable matter)에서 squalene을 식별했음. - Folstar (1985)의 연구

▨ 커피 왁스뿐만 아니라, wax-free coffee oil에서

▨ 많은 odd and even chain-length alkanes를 모두 발견, 보고. - Kurt and Speer (1999)의 연구

▨ 분자식 C19H30O2를 가지는 새로운 성분을 검출하여 분리해냈음.

▨ 이 구조는 알려진 coffee diterpene cafestol와 비슷함.

▨ 가장 중요한 차이는

furan ring의 부재와

carbon atom C10.에서의 one methyl group의 위치임,

▨ 이 새로운 성분을 coffeadiol이라고 명명함. - Kölling-Speer et al. (2005)의 연구

▨ 40℃에서 보관된 습식 처리된 콜롬비아 아라비카 커피 생두에서

분자식 C22H28O2을 가지는 또 다른 새로운 물질을 식별해냈음.

▨ 이 물질의 구조는 coffee diterpene kahweol과 비슷하지만

furan group 대신에 aromatic ring이 있는 구조.

▨ 이 성분은 arabiol I 이라고 명명되었음.

11. Volatile constituents

- 커피 생두 내에서 약 230개의 휘발성 물질들이 식별되어 왔음.

(Boosfeld & Vitzthum, 1995; Holscher & Steinhart, 1995; Cantergiani et al., 1999) - Arabica 커피와 Robusta 커피는 비슷하지만, 아라비카 커피들이

➡ 터핀류의 함량이 더 높고(a large content of terpenes),

➡ 아로마 화합물이 더 적게 구분되었다(Holscher, W. and H. Steinhart, 1995). - 커피 생두의 휘발성 물질들의 함량 범위는

➡ 생두 프로세싱에 의해 영향을 받으며

➡ 생두 품질 평가를 위해 사용될 수 있다. - 결점두들의 냄새는 특정한 성분들과 연결되어져 왔다.

12. Contaminants

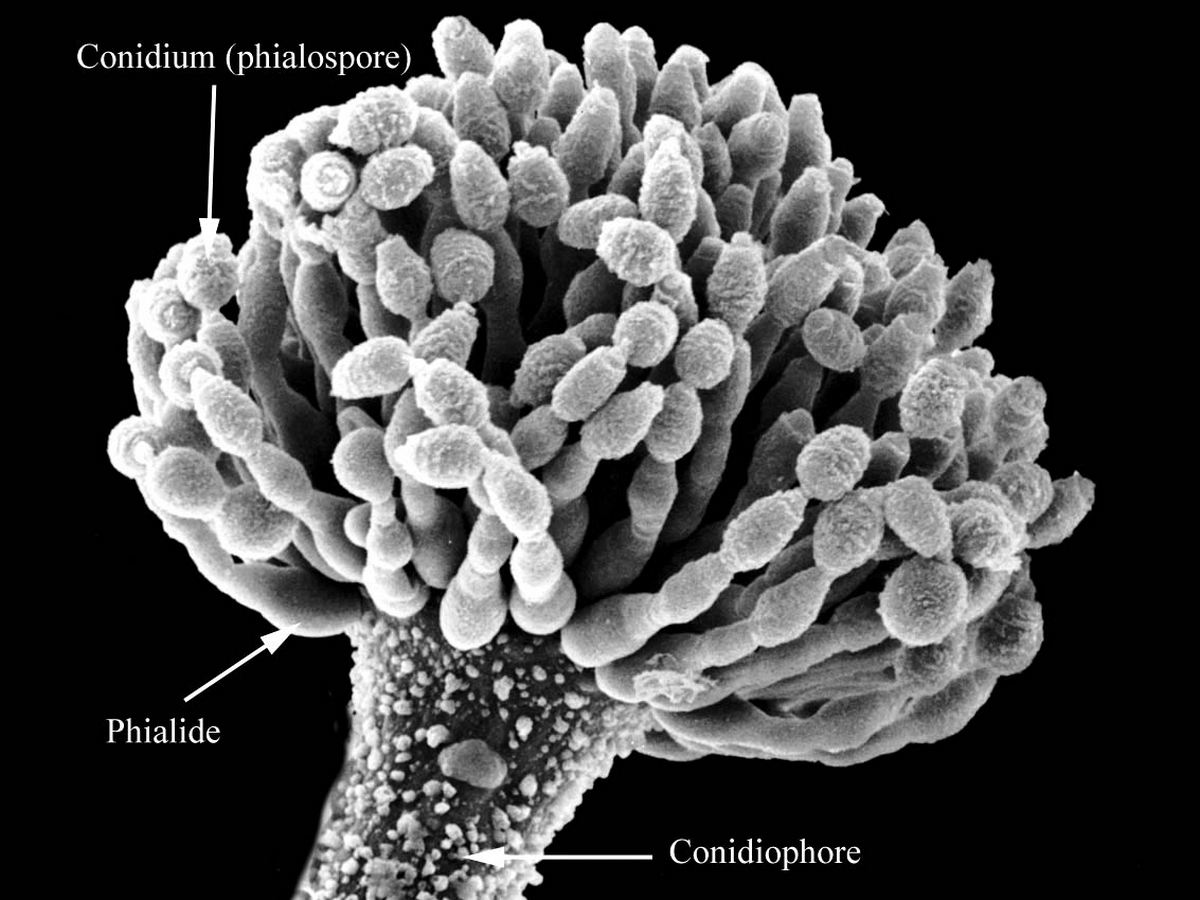

12.1 Mycotoxins

커피 생두를 오염시킬 수 있는 몇 가지 미코톡신의 우연한 발생 알려지기 시작한 시기 ➡ 1970년대 초

Mycotoxins ➡ 미코톡신, 마이코탁신 = 진균독(眞菌毒), 곰팡이 독,

곰팡이가 번식하여 생산하는, 중독성이 있는 독소.

여러 미코톡신의 우연한 발생이 커피 생두를 오염시킬 수 있다.

Mycotoxins의 종류

▣ Sterigmatocystine (스테리그마토시스틴)

▣ Aflatoxin B (아프라톡신 B)

▣ Ochratoxin A (OTA) 오크라톡신 A

Aflatoxins

- Aflatoxins 아프라톡신은

▣ 많은 Aspergillus 진균 종들에 의해 자연적으로 발생하는 미코톡신이며,

▣ 가장 악명 높은 것은 ➡ Aspergillus flavusa와

➡ Aspergillus parasiticus이다.

▣ 아프라톡신은 ➡ 독성물질이며, 대부분의 발암물질 중의 하나이다.

▣ 아프라톡신은 ➡ 인체에 들어오면,

➡ 간에 의해서 반응 중간체(reactive intermediate)인

Aflatoxin M1 에폭시드로 대사된다. - 특히 Aflatoxin B

➡ 때때로 커피 생두에서 발견되어 왔음.

➡ 매우 작은 량으로

대중 건강에 실질적인 우려가 분명히 없음

➡ 음료에서도 마찬가지 (Nakajima et al., 1997). - 추가적인 정보를 위한 도움이 되는 사이트 = http://www.romerlabs.com/mycotoxins.html

Sterigmatocystine

- Sterigmatocystine (스테리그마토시스틴)

▣ Sterigmatocystine은 the fungi genus Aspergillus.로부터 유발되는 dermatoxin 형의 독이다.

▣ 그 중에서도 주로 fungi Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus versicolor에 의해 생산된다.

▣ 일상에서 이는 곰팡이 쓴 치즈 덩어리에 나타난다.

▣ 아주 극심하게 오염되어서 소비하기에 분명히 적합하지 못한 콩에서만 발견됨.

▣ 커피와 실무적 관련성은 적음. - Sterigmatocystine은

▣ 곰팡이 쓴 곡물에서, 곰팡이 핀 커피 생두, 그리고 치즈에서 보고된 바 있다.

▣ Aflatoxins 보다는 훨씬 덜 자주 발생한다.

▣ aflatoxin B1과 비슷하게 강력한 간암 발암성 물질이다.

▣ 현대의 지식으로는 특수하거나 비정상적인 상황에 있는

소비자들에게 더 이상 위험이 아닌 것으로 생각될 수 있다.

Ochratoxin A (OTA)

- Ochratoxin A (OTA) 감염은

▣ 지난 십 수년간 커피의 OTA 감염은 집중적 연구 주제이었음.

▣ 여러 개선된 분석기법들로 인해서

커피 생두 내의 OTA가 모두 로스팅 동안에 파괴되는 것만은 아니라는 사실이 알려졌음.

▣ Bucheli & Taniwaki (2002)의 연구 - 이 문제에 관한 포괄적 리뷰 발표 - WHO(세계보건기구) 등에서는

오크라톡신 A를 DDT, aflatoxin M1, chloroform과 함께

발암 가능성이 있는 물질인 독성물질 2군 B로 분류하고 있으며

aflatoxin 다음으로 중요한 곰팡이 독소임. - 오크라 톡신은

▣ 오크라톡신 A, B, C, 4 하이드록시오크라톡신A 등 17종의 유사체가 알려져 있음.

▣ 이 중 독성이 가장 강한 것은 오크라톡신 A로서 이것을 일반적으로 오크라톡신이라 함. - 커피에서 OTA를 생산하는 것으로 알려진 것으로 파악된 곰팡이 종들 (아래 사진 참조)

▣ Aspergillus ocharaceus,

▣ Aspergillus carbonarius,

▣ Aspergillus niger

- Ochratoxin A (OTA)으로의 구체적인 오염 시기와 장소는

▣ 명확하게 식별된 것이 없음.

▣ 내추럴 커피나 습식법 처리된 커피나 모두 곰팡이 공격의 위험에 있는 것으로 보임.

▣ 습식법 처리 커피는 OTA에 감염된 것으로 거의 발견되지 않고 있음.

OTA 오염의 위험을 최소화시킬 수 있는 건전한 농경/제조 실무 방법들 (Teixeira et al, 2001; Viani, 2002)

▨ 신선한 체리의 보관

● OTA 감염 위험을 증가시키는 요인들 :

익은 체리와 너무 많이 익은 체리들을 직사광선 하에서 수일 동안 쌓아두거나

혹은 플라스틱 백에 보관하는 것

● 프로세싱 전에 생 체리의 보관을 피하는 것이

커피 미각적 품질 뿐만 아니라 OTA 감염 위험을 경감시킬 수 있음.

▨ 건조

● 건조가 시작된 후에, 로스팅까지 어느 시간이든 water activity 0.80에서 보낸 시간 길이가

곰팡이 성장과 OTA 생성을 결정.

● 더 짧은 파취먼트 sun drying의 측면에서 볼 때,

mechanical drying에 비해 sun drying이 위험을 증가시킬 수 있음.

● 미각적 품질은 정규의 오랜 건조과정을 요하지만,

동시에 OTA 오염 위험성의 축소를 위해서는 빠른 건조가 좋다.

● 따라서, 건조 과정은 이 두 요구사항들을 잘 조정하도록 최적화될 필요가 있다.

▨ 허스크

● 오염의 시작은 Husk 내에서, 적당한 습도 조건 하에서 시작하는 것으로 보이며,

3~4일 정도에 콩에 도달할 수 있다.

● 따라서 OTA 부담을 줄이기 위해서는,

클리닝과 그레이딩 동안에 모든 껍질 물질로부터 커피 콩을 단리시키는 것이 중요하다.

▨ Re-wetting

● 로부스타 커피 생두를 1년간 70% 습도 하에서 30℃까지 올라가는 기온에서 보관하는 것은

OTA 부담의 증가를 가져오지는 않는다고 한다.

● 커피가 응결되고 축축해질 위험을 보인 생산지 국가들로부터 운송 시는

하역 부두까지의 육상 수송 동안에 주로 발생하고, 겨울철에 목적지에 도착하는 경우이다.

● 이런 경우는 적당하게 건조된 커피라도,

온도 변화가 너무 심하면 증발에 이어서 커피의 위쪽 층 부분에 습기가 응결될 수가 있다.

● OTA 감염은 디카페인 프로세스 동안에 발생할 수 있는데,

디카페인된 젖은 커피는 적당하고 빠르게 건조되지 않기 때문이다.

● 배전 이전에 어떠한 단계에서든 다시 젖는 것을 피하는 것이 가장 중요하다.

12.2 PAH

- 그 동안 생두와 배전커피에서 확인되고 계량된

PAH (Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, 다환식 아로마성 탄화수소들)들에는

다음과 같은 것들이 있다 ;

⊙ fluoranthen

⊙ pyrene

⊙ benz[a]fluoranthene

⊙ perylene

⊙ indenol91,2,3-cd]pyrene,

⊙ dibenz[ah]anthracene

⊙ benzo[ghi]perylene - 각 개별 PAH는

➡ 최적 상태가 아닌 로스팅 조건 하에서 연료에 의해서도 형성될 수 있고

➡ 커피 콩에 의해서도 형성될 수 있다. - Klein et al. (1993)의 연구

배전되지 않은 커피와 배전된 커피의 PAH 함량 비교를 해보면,

➡ 배전된 커피의 PAH 함량을 결정하는 것은

➡ 로스팅 최적화 후의 로스팅 과정이라기 보다는

➡ 원재료의 PAH 함량이다. - 생두의 오염은

➡ 자동차의 배기가스 때문이거나 혹은

➡ 오염된 마포 자루나 사이잘 포대에 넣어 운반하는 것이 원인일 수 있다. - 그런 섬유들은

➡ batching oil (軟麻油)로 돌리기 전에 처리되어야 한다.

콩 오염이 발전되기 전에, batching oil은 보통 통제되지 않은 오일 부분으로 구성될 수 있으며,

심지어는 폐기된 모터 오일일 수도 있다. - 오염은 PAH profile을 분석함으로서 식별된다.

- 엄격한 규정이 서명되고, 이제는 포대 제조업자들에 의해 고수되며,

- 이들은 일반적으로 GMP에 따라서 자루 꼬리표를 준비하여 표시한다.

12.3 Pesticide residues

- 살충제 잔여물도 커피 생두의 오염 물질 가운데 하나이다.

- 열매 내의 콩을 덮고 있는 보호층 때문에,

➡ 생두 내에 존재하는 살충제 수준은 매우 낮다. - Cetinkaya (1988)는

➡ 11개 국가들로부터 수입된 커피 생두 샘플들 50가지에서

➡ oragnochlorine 또는

organophosphorus 살충제 잔여물을 검출할 수 없었다.

References and Further Reading

- Aeschbach R., Kusy A. and Maier H.G. (1982) Diterpenoide in Kaffee. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 175, 337–341.

- Amorim H.V., Cruz A.R., St Angelo A.G. et al. (1977) Biochemical, physical and organoleptic changes during raw coffee quality deterioration. Proc. 8th ASIC Coll., pp. 183–186.

- Amorim H.V., Teixeira A.A., Moraes R.S., Reis A.J., Pimentel-Gomes F. and Malavolta E. (1973) Studies on the mineral nutrition of coffee. XXVII. Effect of N, P and K fertilization on the macro and micro nutrients of coffee fruits and on the beverage quality. An. Esc. Sup. Agr. LQ (Piracicaba) 20, 323–333.

- Anon. (1997) Special workshop on the enhancement of coffee quality by reduction of mould growth. Proc. 17th ASIC Coll., pp. 367–369, and following articles.

- Aoyama M., Maruyama T., Kanematsu H., Niiya I., Tsukamoto M., Tokairin S. and Matsumoto T. (1988) Studies on the improvement of antioxidant effect of tocopherols. XVII. Synergistic effect of extracted components from coffee beans. Yukagaku 37, 606–612.

- Arnold U. (1995) Nachweis von Aminosäureveränderungen und Bestimmung freier Aminosäuren in Rohkaffee, Beiträge zur Charakterisierung von Rohkaffeepeptiden. Thesis, University of Dresden.

- Bähre F. (1997) Neue nichtflü chtige Säuren im Kaffee. Thesis, Technical University of Braunschweig.

- Bähre F. and Maier H.G. (1999) New non-volatile acids in coffee. Dtsche Lebensm.-Rundsch. 95, 399–402.

- Becker R., Döhla B., Nitz S. and Vitzthum O.G. (1987) Identification of the ‘peasy’ off-flavour note in central African coffees. Proc. 12th ASIC Coll., pp. 203–215.

- Bengis R.O. and Anderson R.J. (1932) The chemistry of the coffee bean. I. Concerning the unsaponifiable matter of the coffee bean oil. Extraction and properties of kahweol. J. Biol. Chem. 97, 99–113.

- Bertholet R. and Hirsbrunner P. (1984) Preparation of 5-hydroxytryptamine from coffee wax. European Patent 1984–104 696.

- Blanc M., Pittet A., Muñoz-Box R. and Viani R. (1998) Behavior of ochratoxin A during green coffee roasting and soluble coffee manufacture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 673–675.

- Blanc M., Vuataz G. and Hickmann L. (2001) Green coffee transport trials. Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CD-ROM.

- Boosfeld J. and Vitzthum O.G. (1995) Unsaturated aldehydes identification from green coffee. J. Food Sci. 60, 1092–1096.

- Bouyjou R., Fourny G. and Perreaux D. (1993) Le goôt de pomme de terre du café arabica au Burundi. Proc. 15th ASIC Coll., pp. 357–369.

- Bradbury A.G.W. and Balzer H.H. (1999) Carboxyatractyligenin and atractyligenin glycosides in coffee. Proc. 18th ASIC Coll., pp. 71–77.

- Bradbury A.G.W. and Halliday D.J. (1987) Polysaccharides in green coffee beans. Proc. 12th ASIC Coll., pp. 265–269.

- Bradbury A.G.W. and Halliday D.J. (1990) Chemical structures of green coffee bean polysaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 38, 389–392.

- Bucheli P. and Taniwaki M.H. (2002) Research on the origin, and the impact of postharvest handling and manufacturing on the presence of ochratoxin A in coffee. Food Addit. Contam. 19 (7), 655–665.

- Bucheli P., Kanchanomai C., Meyer I. and Pittet A. (2000) Development of ochratoxin A during Robusta

(Coffea canephora) coffee cherry drying. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 1358–1362. - Bucheli P., Meyer I., Pittet A., Vuataz G. and Viani R. (1998) Industrial storage of green robusta coffee under tropical conditions and its impact on raw material quality and ochratoxin A content. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 4507–4511.

- Calzolari C. and Cerma E. (1963) Sulle sostanze grasse del caffè. Riv. Ital. Sostanze Grasse 40, 176–180.

- Cantergiani E., Brevard H., Amado R., Krebs Y., Feria-Morales A. and Yeretzian C. (1999) Characterisation of mouldy/earthy defect in green Mexican coffee. Proc. 18th ASIC Coll., pp. 43–49.

- Carisano A. and Gariboldi L. (1964) Gaschromatographic examination of the fatty acids of coffee oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 15, 619–622.

- Castel de Menezes H. and Clifford M.N. (1988) The influence of stage of maturity and processing method on the relation between the different isomers of caffeoilquinic acid in green coffee beans. Proc. 12th ASIC Coll., pp. 377–381.

- Cetinkaya M. (1988) Organophosphor- und Organochlorpestizidrückstände in Rohkaffee. Dtsch. Lebensm. Rundsch. 84, 189–190.

- Chakravorty P.N., Levin R.H., Wesner M.M. and Reed. G. (1943b) Cafesterol III. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 65, 1325–1328.

- Chakravorty P.N., Wesner M.M. and Levin R.H. (1943a) Cafesterol II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 65, 929–932.

- Clarke R.J. and Vitzthum O.G. (eds) (2001) Coffee – Recent Developments. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

- Clifford M.N. (1985) Chemical and physical aspects of green coffee and coffee products. In M.N. Clifford and K.C. Willson (eds), Coffee: Botany, Biochemistry and Production of Beans and Beverage. Westport, CT: AVI, pp. 314–315.

- Clifford M.N. (1999) Chlorogenic acids and other cinnamates. Nature, occurrence and dietary burden. J. Sci. Food Agric. 79, 362–372.

- Clifford M.N. and Ohiokpehai O. (1983) Coffee astringency. Analyt. Proc. 20, 83–86.

- Clifford M.N., Kazi T. and Crawford S. (1987) The content and washout kinetics of chlorogenic acids in normal and abnormal green coffee beans. Proc. 12th ASIC Coll., pp. 221–228.

- Finnegan R.A. and Djerassi C. (1960) Terpenoids XLV. Further studies on the structure and absolute configuration of cafestol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 82, 4342–4344.

- Fischer M., Reimann S., Trovato V. and Redghwell R.J. (2000) Structural aspects of polysaccharides from arabica coffee. Proc 18th ASIC Coll., pp. 91–94.

- Flament I. (2002) Coffee Flavour Chemistry. New York: John Wiley.

- Folstar P. (1985) Lipids. In R.J. Clarke and R. Macrae (eds), Coffee: Volume 1 – Chemistry. London: Elsevier Applied Science, pp. 203–222.

- Folstar P., Pilnik W., de Heus J. G. and Van der Plas H. C. (1975) The composition of fatty acids in coffee oil and wax. Lebensm. Technol. 8, 286–288.

- Folstar P., Schols H.A., Van der Plas H.C., Pilnik W., Landherr C.A. and Van Vildhuisen A. (1980) New tryptamine derivatives isolated from wax of green coffee beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 28, 872–874.

- Folstar P., Van der Plas H.C., Pilnik W. and de Heus J.G. (1977) Tocopherols in the unsaponifiable matter of coffee

bean oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 25, 283–285. - Frank J.M. (2001) On the activity of fungi in coffee in relation to ochratoxin A production. Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CD-ROM.

- Franz H. and Maier H.G. (1993) Inositol phosphates in coffee and related beverages. I. Identification and methods of determination. Dtsche Lebensm.-Rundsch. 89, 276–282.

- Franz H. and Maier H.G. (1994) Inositol phosphates in coffee and related beverages. II. Coffee beans. Dtsche Lebensm.-Rundsch. 90, 345–349.

- Frega N., Bocci F. and Lercker G. (1994) High resolution gas chromatographic method for determination of Robusta coffee in commercial blends. J. High Resolution Chromatogr. 17, 303–307.

- Full G., Lonzarich V. and Suggi L.F. (1999) Differences in chemical composition of electronically sorted green coffee beans. Proc. 18th ASIC Coll., pp. 35–42.

- Grob K., Biedermann M., Artho A. and Egli J. (1991a) Food contamination by hydrocarbons from packaging materials determined by coupled LC–GC. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 193, 213–219.

- Grob K., Lanfranchi M., Egli J. and Artho A. (1991b) Determination of food contamination by mineral oil from jute sacks using coupled LC-GC. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 74, 506–512.

- Guyot B., Petnga E. and Vincent J.C. (1988a) Analyse qualitative d’un café Coffea canephora var. robusta. I. Evolution des caractères physiques et organoleptiques. Café Cacao The´ 32, 127–140.

- Guyot B., Cochard B. and Vincent J.C. (1991) Détermination quantitative du diméthylsulfure et du diméthyldisulfure dans lárôme de café. Café Cacao The´ 35, 49–56.

- Harms U. (1968) Beiträge zum Vorkommen und zur Bestimmung von Carbonsäure-5-hydroxy-tryptamiden in Kaffeebohnen. Thesis, University of Hamburg.

- Harms U. and Wurziger J. (1968) Carboxylic acid 5-hydroxytryptamides in coffee beans. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 138, 75–80.

- Haworth R.D. and Johnstone R.A.W. (1957) Cafestol Part. II. J. Chem. Soc. (Lond.), pp. 1492–1496.

- Holscher W. and Steinhart H. (1995) Aroma compounds in green coffee. In G. Charalambous (ed.), Food Flavours: Generation, Analysis and Process Influence. 37 A. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, pp. 785–803.

- Horman I. and Viani R. (1972) The nature and conformation of the caffeinechlorogenate complex of coffee. J. Food Sci. 37, 925–927.

- Hunziker H.R. and Miserez A. (1979) Bestimmung der 5-Hydroxytryptamide in Kaffee mittels Hochdrück-Flüssigkeitschromatographie. Mitt. Geb. Lebensum. Unters. Hyg. 70, 142–152.

- Illy A. and Viani R. (eds) (1995) Espresso Coffee. The Chemistry of Quality. London: Academic Press, p. 29.

- Ismayadi C. and Zaenudin. (2001) Toxigenic mould species infestation in coffee beans taken from different levels of production and trading in Lampung – Indonesia (2001). Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CD-ROM.

- Itoh T., Tamura T. and Matsumoto T. (1973a) Sterol composition of 19 vegetable oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 50, 122–125.

- Itoh T., Tamura T. and Matsumoto T. (1973b) Methylsterol compositions of 19 vegetable oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 50, 300–303.

- Jobin P. (1982) Les Cafeés produits dans le monde. Le Havre: Jobin. Joosten H.M.L.J., Goetz J., Pittet A.,

- Schellenberg M. and Bucheli P. (2001) Production of ochratoxin A by Aspergillus carbonarius on coffee cherries. Int. J. Food Microb. 65, 39–44.

- Jouanjan F. (1980) Transport maritime du café vert et conte´neurisation. Proc. 9th ASIC Coll., pp. 177–188.

- Kampmann B. and Maier H.G. (1982) Säuren des Kaffees. I. Chinasäure. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 175, 333–336.

- Kappeler A.W. and Baumann T.W. (1986) Purine alkaloid pattern in coffee beans. Proc. 11th ASIC Coll., pp. 273–279.

- Kaufmann H.P. and Hamsagar R.S. (1962a) Zur Kenntnis der Lipoide der Kaffeebohne. I. Über Fettsäure-Ester des Cafestols. Fette Seifen Anstrichmittel 64, 206–213.

- Kaufmann H.P. and Hamsagar R.S. (1962b) Zur Kenntnis der Lipoide der Kaffeebohne. II. Die Veränderung der Lipoide bei der Kaffee-Röstung. Fette Seifen Anstrichmittel 64, 734–738.

- Klein H., Speer K. and Schmidt E.H.F. (1993) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in raw and roasted coffee. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 36, 98–100.

- Kölling-Speer I. and Speer K. (1997) Diterpenes in coffee leaves. Proc. 17th ASIC Coll., pp. 150–154.

Kölling-Speer I., Kurzrock T. and Speer K. (2001) Contents of diterpenes in green coffees. Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CD-ROM. - Kölling-Speer I., Strohschneider S. and Speer K. (1999) Determination of free diterpenes in green and roasted coffees. J. High Resolution Chromatogr. 22, 43–46.

- Kurzrock T. and Speer K. (1997a) Fatty acid esters of cafestol. Proc. 17th ASIC Coll., pp. 133–140.

- Kurzrock T. and Speer K. (1997b) Identification of cafestol fatty acid esters. In R. Amado` and R. Battaglia (eds), Proc. Euro Food Chem. IX (Interlaken), Volume 3, pp. 659–663.

- Kurzrock T. and Speer K. (2001a) Diterpenes and diterpene esters in coffee. Food Rev. Int. 17, 433–450.

- Kurzrock T. and Speer K. (2001b) Identification of kahweol fatty acid esters in arabica coffee by means of LC/MS. J. Sep. Sci. 24, 843–848.

- Labuza T.P., McNally L., Gallager D. et al. (1972) Stability of intermediate moisture foods. 1. Lipid oxidation. J. Food Sci. 37, 154–159.

- Lehmann G., Neunhoeffer O., Roselius W. and Vitzthum O. (1968) Antioxidants made from green coffee beans and

their use for protecting autoxidizable foods. German Patent 1,668,236. - Levi C.P., Trenk H.L. and Mohr H.K. (1974) Study of the occurrence of ochratoxin A in green coffee beans. J. Assoc. Official Analyt. Chemists 57, 866–870.

- Lipke U. (1999) Untersuchungen zur Charakterisierung von Rohkaffeepeptiden. Thesis, University of Dresden.

- Ludwig H., Obermann H. and Spiteller G. (1975) New diterpenes found in coffee. Proc. 7th ASIC Coll., pp. 205–210.

- Lüllmann C. and Silwar R. (1989) Investigation of mono- and disaccharide content of arabica and robusta green coffee using HPLC. Lebensm. Gericht. Chem. 43, 42–43.

- Maier H.G. (1981) Kaffee. Berlin and Hamburg: Paul Parey.

- Maier H.G. and Wewetzer H. (1978) Bestimmung von Diterpen-Glykosiden im Bohnenkaffee. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 167, 105–107.

- Mariani C. and Fedeli E. (1991) Sterols of coffee grain of arabica and robusta species. Rivista Ital. Sostanze Grasse 68, 111–115.

- Moraes R.M., Angelucci E., Shirose T. and Medina J.C. (1973) Soluble solids determination in arabica and robusta

coffees. Coll. Inst. Techn. Alim. (Campinas), 5, 199–221. - Moret S., Grob K. and Conte L.S. (1997) Mineral oil polyaromatic hydrocarbons in foods, e.g. from jute bags, by on-line LC-solvent evaporation (SE)-LC-GC-FID. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 204, 241–246.

- Nagasampagi B.A., Rowe J.W., Simpson R. and Goad L.J. (1971) Sterols of coffee. Phytochemistry 10, 1101–1107.

- Naish M., Clifford M.N. and Birch G.G. (1993) Sensory astringency of 5-Ocaffeoylquinic acid, tannic acid and grapeseed tannin by a time-intensity procedure (1993). J. Sci. Food Agric. 61, 57–64.

- Nakajima M., Tsubouchi H., Miyabe M. and Ueno Y. (1997) Survey of aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A in commercial green coffee beans by high-performance liquid chromatography linked with immunoaffinity chromatography. Food Agric. Immunol. 9, 77–83.

- Noyes R.M. and Chu C.M. (1993) Material balance on free sugars in the production of instant coffee. Proc. 14th ASIC Coll., pp. 202–210.

- Obermann H. and Spiteller G. (1976) Die Strukturen der Kaffee-Atractyloside. Chem. Ber. 109, 3450–3461.

- Ogawa M., Herai Y., Koizumi N., Kusano T. and Sano H. (2001) 7-Methylxanthine methyltransferase of coffee plants – gene isolation and enzymatic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 8213–8218.

- Ogawa M., Kamiya C. and Iida Y. (1989) Contents of tocopherols in coffee beans, coffee infusions and instant coffee. Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi 36, 490–494.

- Parliment T.H. (2000) An overview of coffee roasting. In T.H. Parliment, CT. Ho, P. Schieberle (eds), Caffeinated Beverages, Health Benefits, Physiological Effects, and Chemistry. ACS symposium series No. 754, pp. 188–201.

- Pettitt B.C. Jr. (1987) Identification of the diterpene esters in arabica and canephora coffees.

J. Agric. Food Chem. 35, 549–551. - Pitt J.I., Taniwaki M.H., Teixeira A.A. and Iamanaka B.T. (2001) Distribution of Aspergillus ochraceus, A. niger and A. carbonarius in coffee in four regions of Brazil. Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CD-ROM.

- Pittet A., Tornare D., Huggett A. and Viani R. (1996) Liquid chromatographic determination of ochratoxin A in pure and adulterated soluble coffee using an immunoaffinity column cleanup procedure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 44, 3564–3569.

- Pokorny J., Nguyen-Huy C., Smidralova E. and Janicek G. (1975) Nonenzymic browning. XII. Maillard reactions in green coffee beans on storage. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 158, 87–92.

- Prodolliet J., Baumgartner M., Martin Y.L. and Remaud G. (1998) Determination of the geographic origin of green coffee by stable isotope techniques. Proc. 17th ASIC Coll., pp. 197–200.

- Quijano Rico M. and Spettel B. (1975) Determinacion del contenido en varios elementos en muestras de cafes de diferentes variedades. Proc. 7th ASIC Coll., pp. 165–173.

- Roselius L. (1937) Die Erfindung des coffeinfreien Kaffes. Chemiker Zeitung 61 (1), 13.

- Runge F. (1820) Neueste phytochemische Entdeckungen 1, 144–159.

- Scholze A. and Maier H.G. (1983) Die Säuren des Kaffees. VII. Ameisen, Äpfel-, Citronen- und Essigsäure. Kaffee Tee Markt 33, 3–6.

- Scholze A. and Maier H.G. (1984) Säuren des Kaffees. VIII. Glycol- und Phosphorsäure. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 178, 5–8.

- Spadone J.C., Takeoka G. and Liardon R. (1990) Analytical investigation of rio off-flavor in green coffee. J. Agric. Food Chem. 38, 226–233.

- Speer K. (1989) 16-O-Methylcafestol – ein neues Diterpen im Kaffee – Methoden zur Bestimmung des

16-O-Methylcafestols in Rohkaffee und in behandelten Kaffees. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 189, 326–330. - Speer K. (1991) 16-O-methylcafestol – a new diterpene in coffee; the fatty acid esters of 16-O-methylcafestol.

In W. Baltes, T. Eklund, R. Fenwick, W. Pfannhauser, A. Ruiter and H.-P. Thier (eds), Proc. Euro Food Chem. VI Hamburg, Germany, Volume 1. Hamburg: Behr’s Verlag, pp. 338–342. - Speer K. (1995) Fatty acid esters of 16-O-methylcafestol. Proc. 16th ASIC Coll., pp. 224–231.

- Speer K. and Mischnick P. (1989) 16-O-Methylcafestol – ein neues Diterpen im Kaffee – Entdeckung und Identifizierung. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 189, 219–222.

- Speer K. and Mischnick-Lübbecke P. (1989) 16-O-Methylcafestol – ein neues Diterpen im Kaffee. Lebensmittelchemie 43, 43.

- Speer K. and Montag A. (1989) 16-O-Methylcafestol – ein neues Diterpen im Kaffee – Erste Ergebnisse: Gehalte in Roh- und Röstkaffees. Dtsch. Lebensm.-Rundsch. 85, 381–384.

- Speer K., Hruschka A., Kurzrock T. and Kölling-Speer I. (2000) Diterpenes in coffee.

In T.H. Parliment, C-T. Ho and P. Schieberle (eds), Caffeinated Beverages, Health Benefits, Physiological Effects, and Chemistry. ACS symposium series No. 754, pp. 241–251. - Speer K., Sehat N. and Montag A. (1993) Fatty acids in coffee. Proc. 15th ASIC Coll., pp. 583–592.

- Speer K., Steeg E., Horstmann P., Kühn T. and Montag A. (1990) Determination and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in native vegetable oils, smoked fish products, mussels and oysters, and bream from the river Elbe. J. High Resolution Chromatogr. 13, 104–111.

- Speer K., Tewis R. and Montag A. (1991a) 16-O-Methylcafestol – ein neues Diterpen im Kaffee – Freies und gebundenes 16-O-Methylcafestol. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 192, 451–454.

- Speer K., Tewis R. and Montag, A. (1991b) 16-O-methylcafestol – a quality indicator for coffee. Proc. 14th ASIC Coll., pp. 237–244.

- Speer K., Tewis R. and Montag A. (1991c) A new roasting component in coffee. Proc. 14th ASIC Coll., pp. 615–621.

- Stennert A. and Maier H.G. (1994) Trigonelline in coffee. II. Content of green, roasted and instant coffee. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 199, 198–200.

- Teixeira A.A., Taniwaki M.H., Pitt J.I., Iamanaka B.T. and Martin C.P. (2001) The presence of ochratoxin A in coffee due to local conditions and processing in four regions in Brazil. Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CDROM.

- Tiscornia E., Centi-Grossi M., Tassi-Micco C. and Evangelisti F. (1979) Sterol fractions of coffee seeds oil (Coffea arabica L.). Rivista Ital. Sostanze Grasse 56, 283–292.

- Trautwein E. (1987) Untersuchungen über den Gehalt an freien und gebundenen Aminosäuren in verschiedenen Kaffeesorten sowie über deren Verhalten während des Röstens. Thesis, University of Kiel.

- Trouche M.-D., Derbesy M. and Estienne J. (1997) Identification of robusta and arabica species on the basis of

16-O-methylcafestol. Ann. Fals. Exp. Chim. 90, 121–132. - Tsubouchi H., Terada H., Yamamoto K., Hisada K. and Sakabe Y. (1988) Ochratoxin A found in commercial roast coffee. J. Agric. Food Chem. 36, 540–542.

- Van der Stegen G.H.D. and Noomen P.J. (1977) Mass-balance of carboxy-5-hydroxytryptamindes (C-5-HT) in regular and treated coffee. Lebensmittelwiss. Technol. 10, 321–323.

- Van der Stegen G.H.D. and Van Duijn, J. (1987) Analysis of normal organic acids in coffee. Proc. 12th ASIC Coll., pp. 238–246.

- Van der Stegen G., Blanc M. and Viani R. (2001) Highlights of the workshop – Moisture management for mould prevention. Proc. 19th ASIC Coll., CD-ROM.

- Viani R. (1993) The composition of coffee. In S. Garattini (ed.), Caffeine, Coffee, and Health. New York: Raven Press, pp. 17–41.

- Viani R. (2002) Effect of processing on ochratoxin A (OTA) content of coffee. Adv. Med. Biol. 504, 189–193.

- Viani R. (2003) Coffee physiology. In Encyclopedia of Food Science and Technology, 2nd edn., Volume 3. London: Elsevier Science, pp. 1511–1516.

- Vincent J.C. (1987) International standardization. In R.J. Clarke and R. Macrae (eds),

Coffee: Volume 1 – Technology. London: Elsevier Applied Science, pp. 28–30. - Vitzthum O.G., Weisemann C., Becker R. and Köhler H.S. (1990) Identification of an aroma key compound in robusta coffees. Café Cacao The´ 34, 27–33.

- Wajda P. and Walczyk D. (1978) Relationship between acid value of extracted fatty matter and age of green coffee beans. J. Sci. Food Agric. 29, 377–380.

- Weidner M. and Maier H.G. (1999) Seltene Purinalkaloide in Röstkaffee. Lebensmittelchemie 53, 58.

- Wettstein A., Spillmann M. and Miescher K. (1945) Zur Konstitution des Cafesterols 6. Mitt. Helv. chim. Acta 28, 1004–1013.

- White D.R. (1995) Coffee adulteration and a multivariate approach to quality control. Proc. 16th ASIC Coll., pp. 259–266.

- Wöhrmann R., Hojabr-Kalali B. and Maier H.G. (1997) Volatile minor acids in coffee. I. Contents of green and roasted coffee. Dtsche Lebensm.-Rundsch. 93, 191–194.

- Wootton A.E. (1971) The dry matter loss from parchment coffee during filed processing. Proc. 5th ASIC Coll., pp. 316–324.

- Zosel K. (1971) Verfahren zur Entcoffeinierung von Rohkaffee. German Patent 2,005,293.

'Coffee Chemistry' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 커피의 탄수화물 (2001) by A.F.W. Bradbury (0) | 2025.03.29 |

|---|---|

| 커피의 화학 (1) | 2025.03.28 |

| Coffee Constituents by Adriana Farah (2012) [2] (0) | 2025.03.24 |

| Coffee Constituents by Adriana Farah (2012) [1] (0) | 2025.03.24 |

| The Complexity of Coffee by Ernesto Illy (2002) (0) | 2025.03.22 |

댓글